You know how sometimes, something just sticks with you?

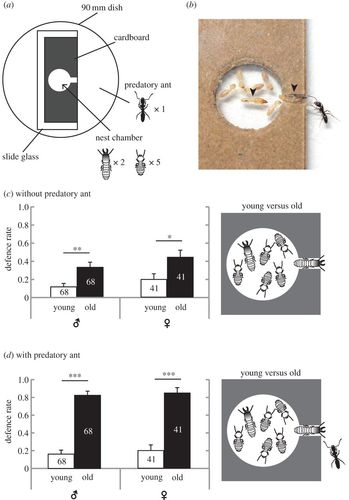

Here’s one of mine: When termites battle predatory ants, the oldest termite citizens form the front line, sacrificing themselves first.

It was so jaw-dropping that I’ve thought about the concept several times. Upon investigation, I learned that termites are considered “eusocial.” Eusociality is defined by cooperative brood care, overlapping generations living within a colony of adults, and a division of labor into reproductive and non-reproductive groups. There’s a form of caste system and individual members of the group sacrifice their freedom and independence in favor of the common good.

There are different points of view on whether humans are eusocial (one example thread). Primarily, though, we can’t organize our society like termites because we care deeply about individual agency. But that doesn’t mean we don’t get into a lot of arguments about the common good.

This little science fact led me down so many paths.

It made me think about politics — it’s usually the elderly that commit the young to wars, quite the polar opposite of termites (although, old and young termites are equally effective fighters, which can’t be said for human beings).

And the climate — it is, again, the elderly who seem to be sacrificing future generations when it comes to climate change. I am clearly not talking about sacrificing lives, but we aren’t even willing to sacrifice SUVs that give us 18 miles per gallon (!) and quarter pounders that are terrible for the environment.

It is perhaps more relevant now with Covid and the controversy about what’s best for everyone during this time. It made me think about the nuclear family, which is still controversial, apparently, with David Brooks arguing that it was a mistake. At this moment in time, more people are likely to agree with him as couples are returning to cohabitate with their parents to better manage the burden of 24×7 childcare combined with 24×7 work.

Every generation seems to be dealing with Covid differently. The elderly are afraid for their lives and health, but are, generationally, sitting on wealth they were able to build during their lifetimes. Meanwhile millennials are facing unemployment having never built a solid foundation to cushion them. The fears are different, the approach is different, and we are all in conflict.

Which brings me to the question — do termites make the sacrifice because it is “their” colony, the one in which they grew up? Much like (most) grandparents would for their grandchildren? Would termites display the same behavior if they were dropped into another colony?

Termite warfare, ageism, and self-sacrifice for the greater good — it’s an idea that expands, and it’s so broad that it leads to a lot of interesting, interconnected things. The concept is also straightforward to understand, unexpected, and emotionally resonant. All the reasons why this idea stuck with me for months.

What random, yet utterly fascinating things do you find yourself thinking about?