Agency

I started writing this post a couple of months ago, when the world was crazy, but much less crazy than it is right now with the Ukrainian invasion. When the macro level is this out of control, when people are forced into situations they didn’t ask for, it drives home the point of what extreme lack of agency looks like. War is a time when individuals lose their sense of agency—over their own lives, and also over the direction of the world.

Agency is the ability of your effort to first affect the condition of your life, and then the condition of the world.

Without agency, you don’t believe that your effort means anything. Agency is tied to your sense of purpose — you can’t fulfill your purpose without agency. At a basic level, you must be able to

- perceive a choice

- make a choice

- act on the choice

- believe that the choice has the possibility to give you the result that you want to see.

This is so fundamental to human potential and achievement that “agency” is a driving characteristic I look for in investments.

In 2020, Nikhil wrote a post on trends for 2021, and he asked people in tech what their thoughts were. My answer was simple: individual agency. I wrote: “The next big thing in 2021 is agency – where people can construct their lives, regardless of location, and find a way to build the career and lifestyle they want.”

Over the last few years, I’ve realized that agency is the unifying idea that underpins Spero’s thesis.

It’s about investing in the things that enable agency. The 3 different components of “things that make life worth living” are all related to people’s agency—their ability to choose what happens in their lives and the world.

- Wellbeing: the agency to live your life with the physically and mentally capability that you choose. To be able to access your data, choose your path to wellbeing, as you define it.

- Sustainability: the agency for people to have a positive impact on the planet, while also choosing abundance. The ability to make informed choices that reflect their values while thriving and enabling the planet to thrive.

- Learning, work, and play: the agency to choose your path, learn what you want to, work on problems that energize you, build the life you want to have, and enjoy yourself with the people that matter.

Agency makes life worth living.

What to Think About When Designing a Profile Page for Your Users

Everyone wants network effects. A profile page can be an essential element to this—just imagine Github or Twitter without a profile page. Would people still join?

While it seems simple on the surface, there are tens (if not hundreds) of decisions that drive a profile page that will deliver value to your users, and therefore to your company.

Let’s dig deeper into some of the key choices and the behaviors they create.

1. What can the user control about her profile page? What does the company control? What can other people do via her profile page?

How much of the content of a user’s profile is self-determined? Some platforms, like Instagram, are all about user-generated content. There’s a lot you can control about what shows up there.

How much of the content is passive? Transaction-based sites, such as Lyft and UpWork, tend to include a lot of passive content—there’s a log of user actions and the feedback related to those. The profile page owner doesn’t control this information; it’s generated and placed there by the company and by other users.

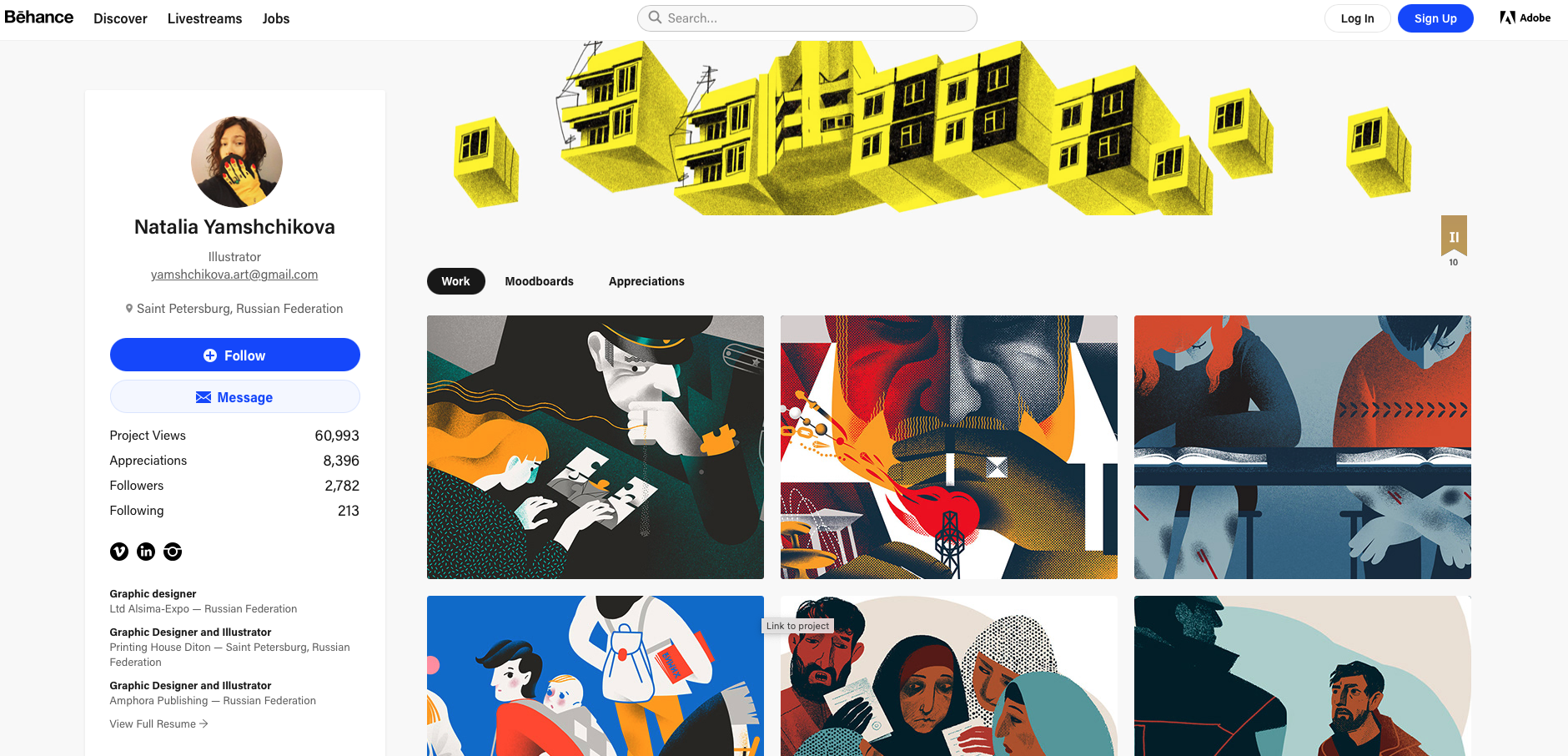

Some platforms are all about allowing users to showcase themselves to the “outside” world. In the case of Behance, the profile page serves as your proof of work or portfolio:

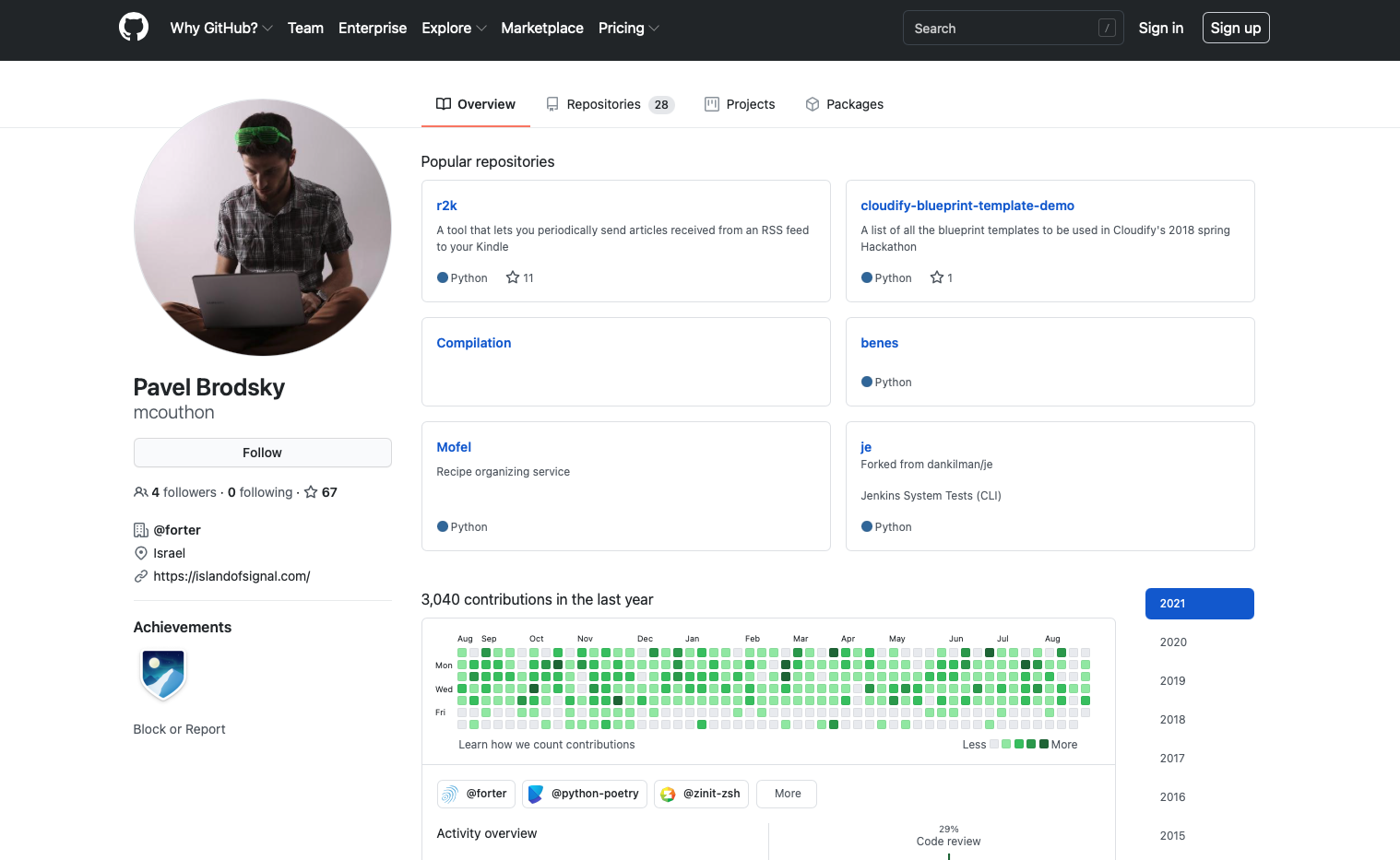

On GitHub, your page is also like a portfolio, but the company automatically adds some cool visualizations of your contribution history:

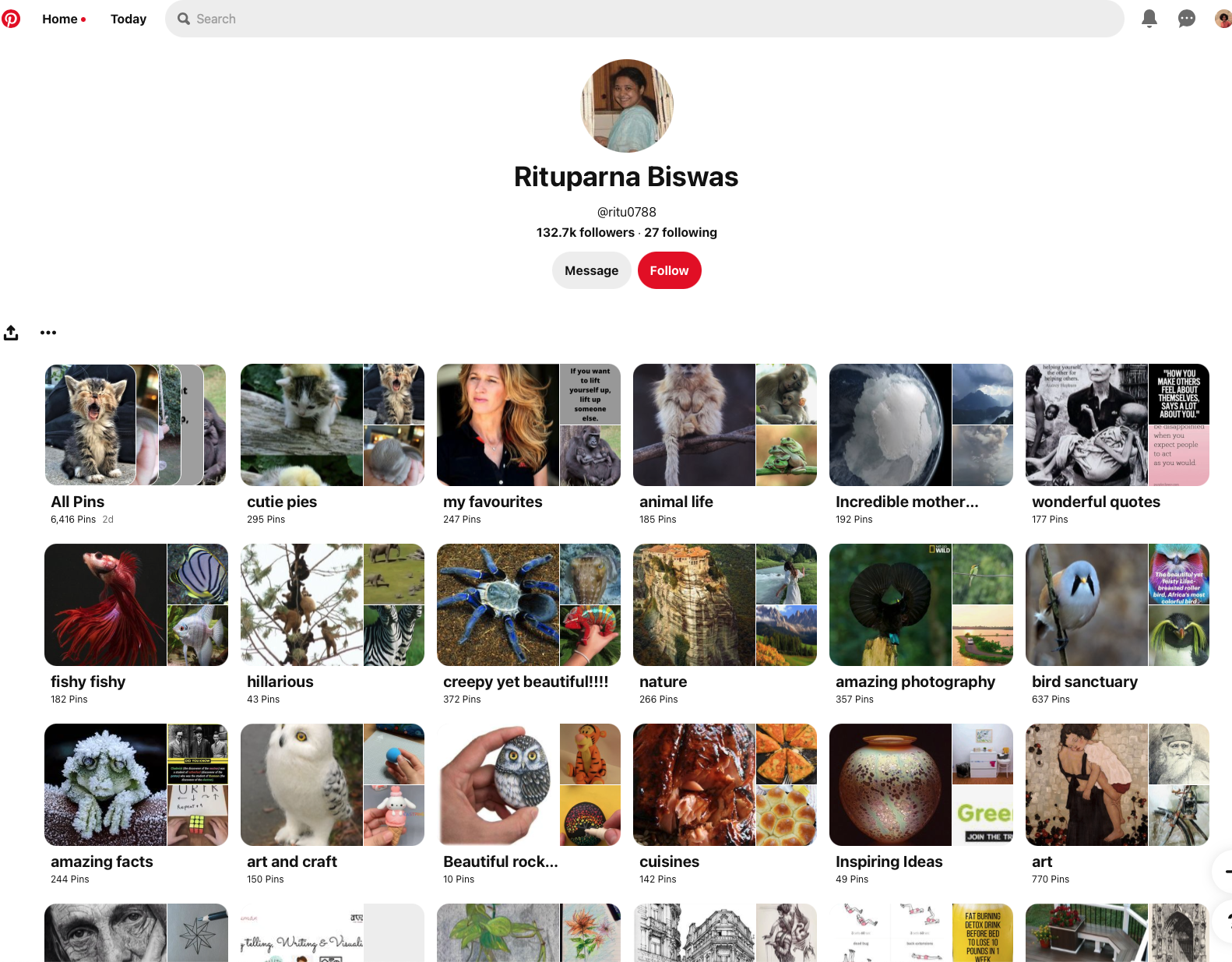

Pinterest is curation vehicle. It’s not a portfolio of your own creations, but it allows users to curate their choice of images and content from around the web:

Once a user starts filling their page, the next step is to think about whether the page can serve as a resource for others as well. Once a profile page starts being a resource for others, everything that is added to the page adds value to the network. This starts to compound pretty quickly.

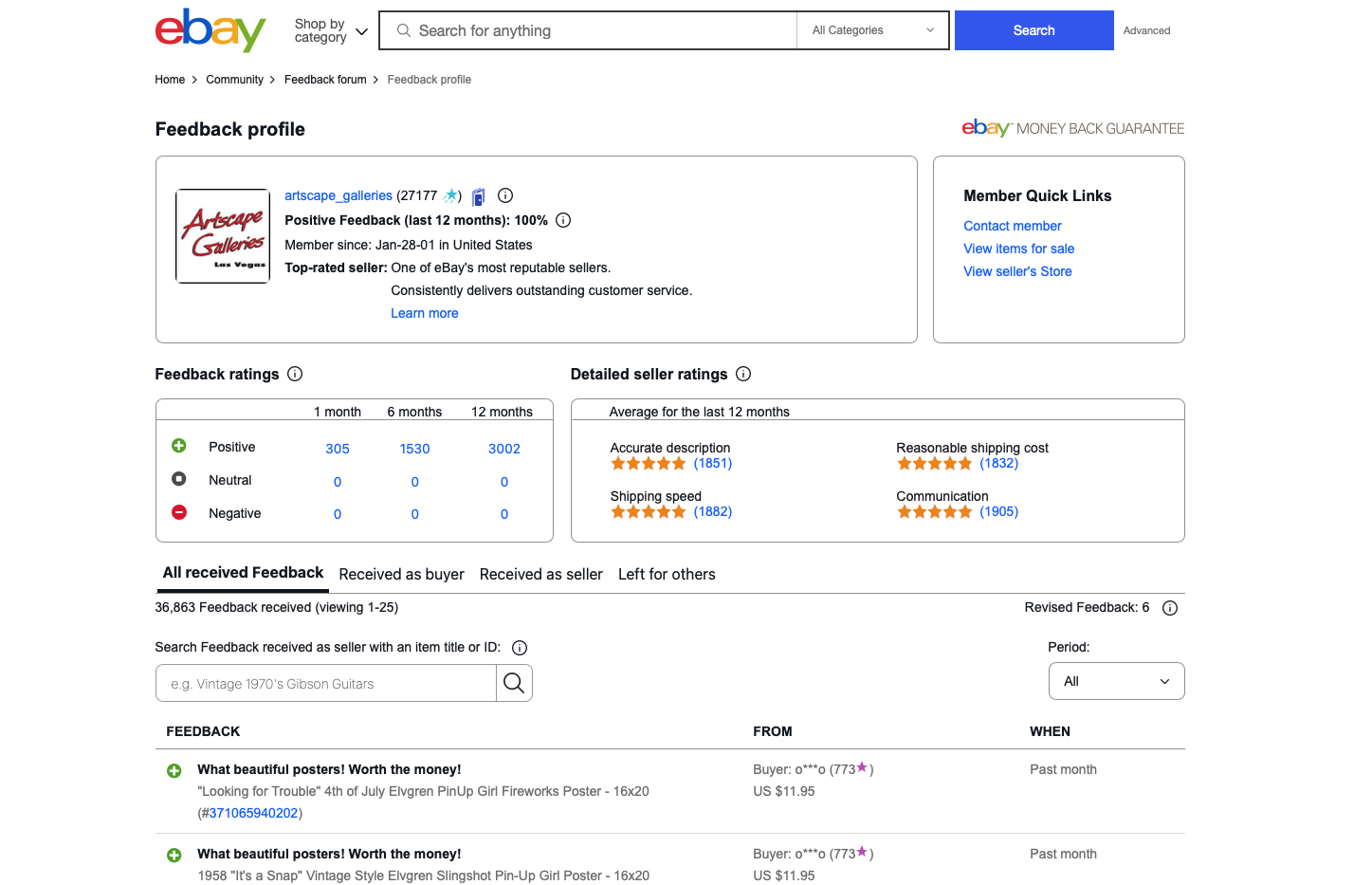

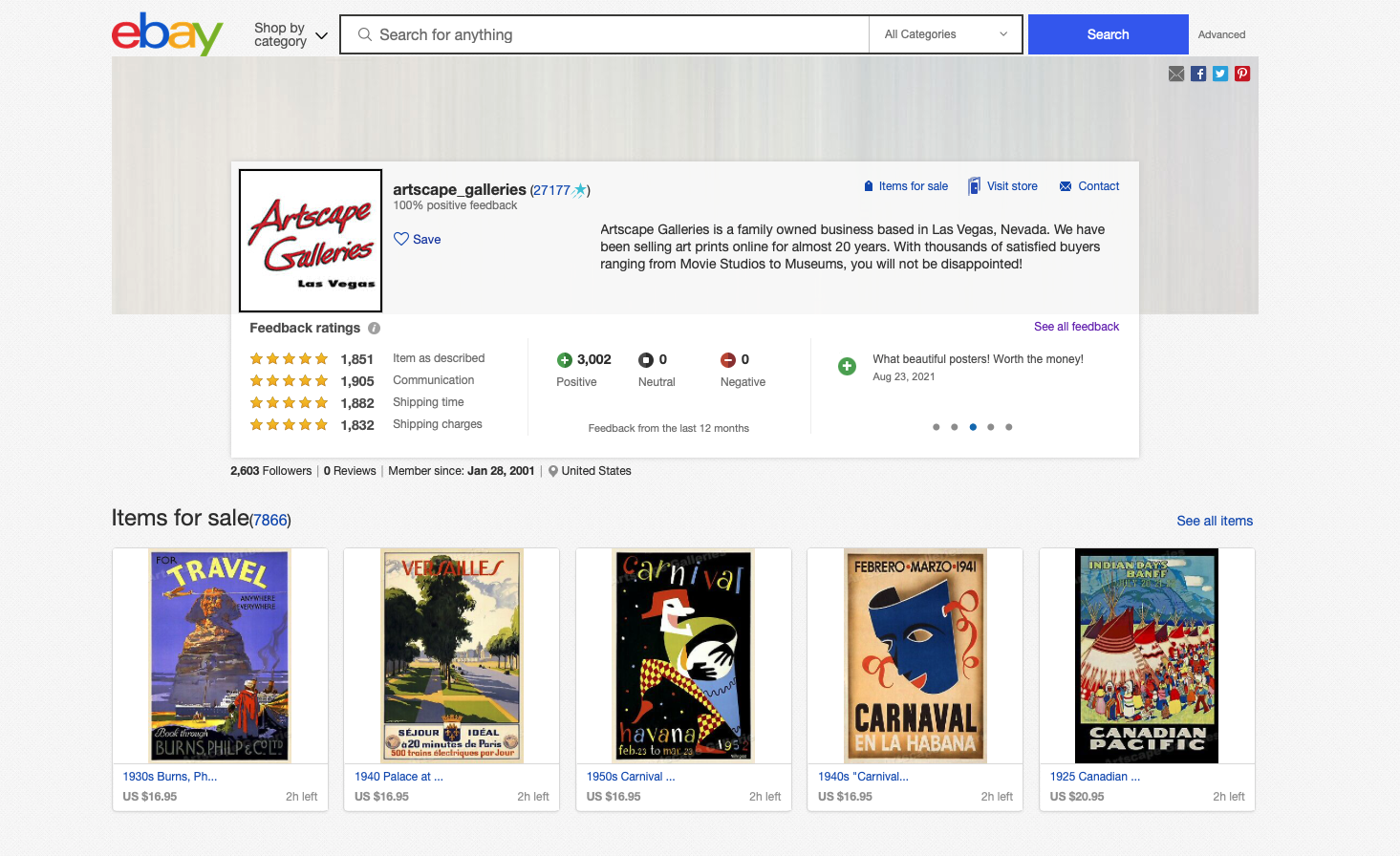

On the other hand, there are sites where the user can’t control the profile page very much at all. For example, on eBay, the original profile page was a purely factual log of interactions and transactions. It was created while you interacted on the site, and you couldn’t curate it. This served a very important function: laying out the buyer’s or seller’s trustworthiness by listing every single transaction and the feedback that came out of it. It’s an enabling page for the whole site (much more so when eBay started at the early stages of the internet). The user didn’t choose how the page was presented to others—it was all controlled by the company, like this:

More recently, eBay made this page into a tab and made the main profile page into something that gives the user a little more control over how they come across:

eBay likely made this change in response to its competitor Etsy. The people who built Etsy understood that control has two elements: one is permissioning (what can you do?), which we have spoken about so far. The second is personalization. Personalization leads to an investment of time and effort, and, eventually, it leads to love for the page and the platform.

When a site limits personalization too much, it can start to to feel utilitarian. A segment of sellers viewed eBay as a business. But they viewed Etsy as a place they could infuse with their personality, vision, and dreams and communicate that to their buyers and their seller friends. This allowed a whole new multi-billion dollar business to be built (Etsy is now over half of eBay’s market cap with with only a handful of the eBay categories).

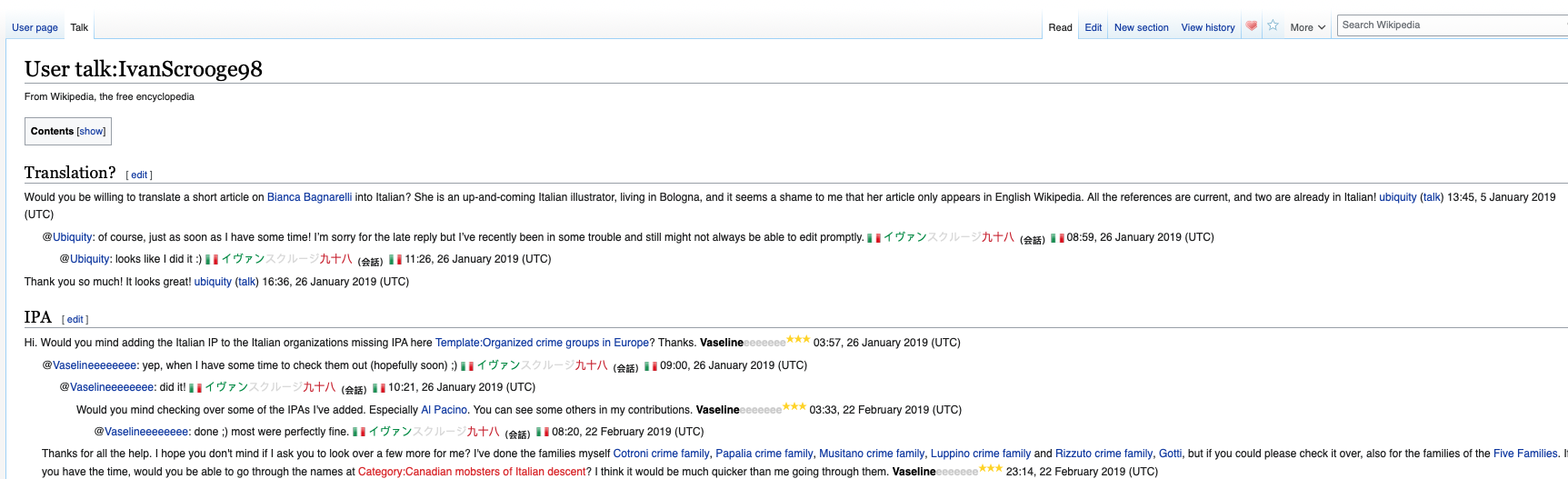

On Wikipedia, users have one profile page where they can describe themselves however they want, and another page called “User Talk” where other users’ comments and questions (e.g. about contributions that you made) are logged and publicly visible.

If you’re building a page which is the spine of the product, it’s important to think through what information you will include on users’ behalf. And what you will allow the user to personalize.

Small decisions can affect user behavior and user emotion, and have large consequences.

2. Should users be anonymous, pseudonymous, or eponymous? Is this a user choice or the company’s choice?

On Twitter, Reddit, Clubhouse etc., you can choose to use your real name or be pseudonymous. The reason I call these pseudonymous is that total anonymity (where the platform doesn’t know who you are) isn’t really possible on a platform that requires a cell phone number since cell phone numbers are usually traceable to a person. On many shopping sites like eBay, you use a “handle” or username, but the platform knows who you are because they require credit card and other information. On Facebook, you’re supposed to be eponymous and use your real name. (Same with Uber and Lyft).

Each of these will lead to types of behavior on the site. When someone is eponymous, most people stay within the bounds of socially acceptable behavior (most of the time). This is positive in terms of hate speech, but it also constraining if the user wants to experiment with creativity or new forms of expression without judgment.

To keep people from pseudonymously impersonating real/famous people, companies can choose to add an extra layer of verification to accounts that get a lot of attention or belong to a celebrity. Eponymous Plus, if you will. A verified account adds benefits to the site by ensuring that the users interacting with them know it’s the actual person and by giving these verified users tools like filters, advanced notifications, and views the plebes cannot access.

Pseudonymous interactions allow more direct, but sometimes harsh or mean, interactions. However, on the positive side, if an artist is exploring a new genre, they may want to experiment pseudonymously. Distancing from real life allows people to interact with others with shared interests without the burden of bringing your “whole self” and everything you have accumulated in your life with you. The site is the final arbiter of excess since they know who the user is and can track them down in cases of illegal activity.

True anonymity can be offered by a platform, but it can lead to a set of behaviors that the company needs to think about. There can be sinister consequences including things like school bullying, predation, and other terrible behavior. For example, Kik became a cesspool that enabled the trading of child porn. The real question is, “What happens if we enable users to do XYZ with no repercussions? And do we want that outcome?”

3. Does every user have the same kind of profile page?

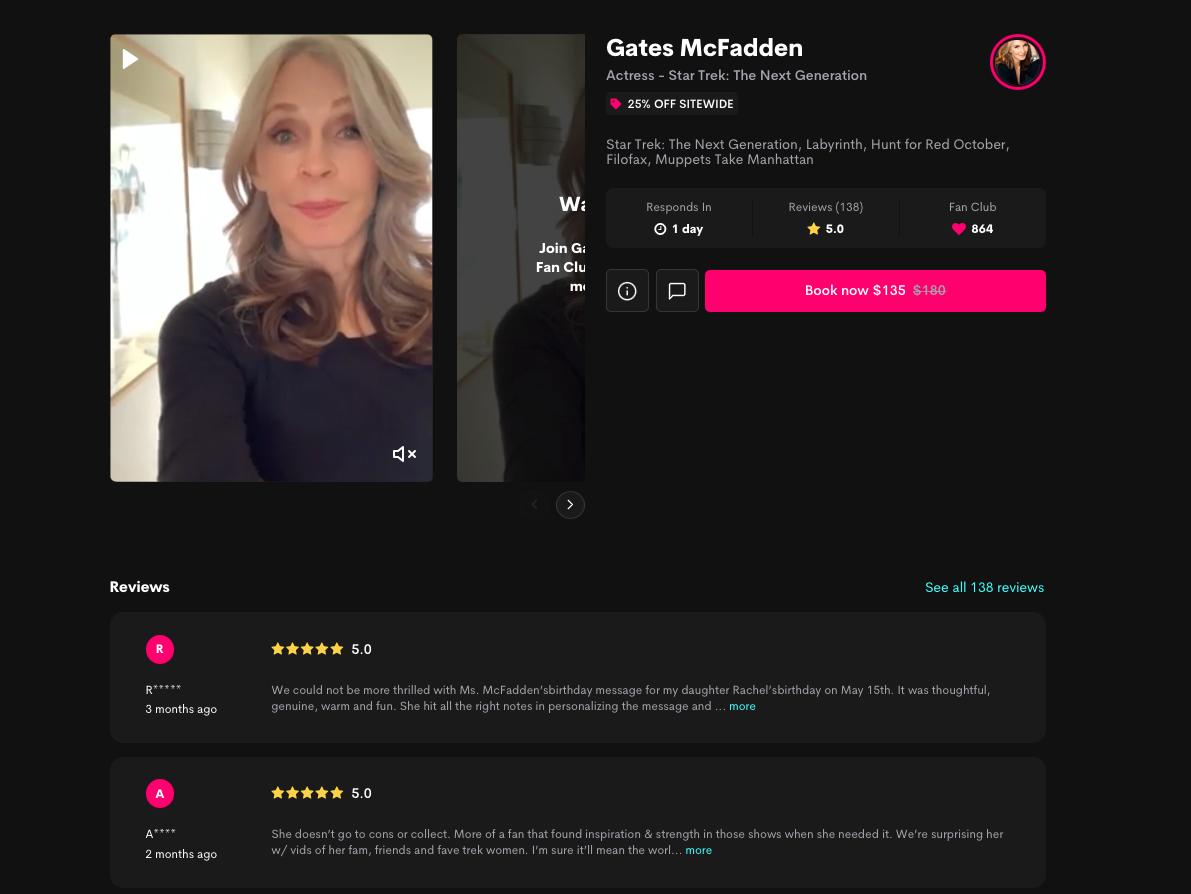

In some communities, some users are faceless by design. For example: Cameo. Cameo is about many, many “normal” individuals who buy cameos from celebrities. The focus is on the celebrities. In Cameo, only the “sellers” have a profile page.

The sellers are famous enough where the people who buy from them are not a validation of the seller’s worth.

On the Seller side, there are reviews, so you know the quality of the work, but you don’t know and can’t see (rightly, in this case), what the final product was. There’s also no way to contact the buyer and ask them questions. User interaction is deliberately limited.

On a platform like UpWork, buyers and sellers have different, but complementary profile pages with a lot of parallels. And on social networks, all profile pages have the same features.

Can users unlock new badges or capabilities?

Sometimes users may be able to do different things on their profile page. This can be seen as a reward (you have been verified by being a good user on this platform, and so have more leeway), or it might be a function of safety on a marketplace. On eBay, you can earn badges based on how many items you’ve sold. Airbnb has “superhosts” who’ve met certain criteria to be labeled as such. This creates a different category of profile page.

Are there privacy settings, and what do they look like?

When it comes to seeing other users’ information, can users select groups to which they’ll reveal more, and other groups to which they’ll reveal less? Is everything public for “everyone on the web” to see, or are there “friends only” options?

There is usually an inverse correlation between how anonymous a user is and how much control they have over their page.

For example, on Facebook, where the user is pushed towards being “a real person” (let’s not get started on how this is violated), you can choose to use the strongest privacy settings. You have levers of control over who sees what information.

On Reddit, where almost everyone is pseudonymous, you need more sunlight to try your best to reduce bad behavior. So here, you can see everyone’s post history without user-set restrictions. Same with eBay, which, more than Reddit, needs a level of trust for you to interact with an unknown person, in an unknown part of the world.

4. How much interpersonal activity is displayed, if any?

Through the profile page, can you look at interactions with other users? On Clubhouse, the profile is a vehicle to interact at the moment that you want to interact, but there’s not much logging of the history of a person’s participation in rooms.

On Twitter, there is a fair bit of interpersonal activity on the site, but only if the user chooses to have the interactions publicly. They could also choose to have the conversations behind the scenes (in DMs). Clubhouse with their private rooms have also enabled this (which in their case, seems to have hurt app usage1 – wouldn’t you rather see people have spats in public and bitch people out to an audience of several thousand?).

Showing interpersonal activity can enhance trust. On a shopping site, repeat purchases are an indication of a happy buyer, but it could also be an indication of a behind-the-scenes relationship. Sunlight is a great disinfectant in these situations.

There’s a spectrum of the importance of the data. On one end is financial data. On the other is likes of photographs (for example). The more closely the site works with deeply personal data, the more user controls of visibility matter. The Venmo situation (where Joe Biden’s transactions were visible), is a great example of this.

The question du jour is does any of this apply to Web3? I’d say yes. Right now, your profile for a Web3 community is distributed between your wallet and your Discord presence(s). This feels pretty basic — if the whole point of many Web3 apps is community, it should be much stronger. And it will be. Tools will develop differently, but the principles outlined here are likely to remain valid.

All of these decisions are crucial because the profile page can become the centerpiece of network effects.

Why? Well, there are two aspects to it:

First — you can’t have a network without nodes in the network. Users are these nodes, and the profile page is how you can identify and locate them. It’s a way, potentially, for users to get introduced to each other and, in doing that, come together into a true network.

If you’re building a platform and aiming to develop a community there, this is especially important. The profile page might be the most essential part of that. It’s central to community as a way for people to understand who another person is and learn what they’re about before and after making a connection.

Second — network effects will start to take off when the profile page itself becomes an asset worth owning. For example: it’s advantageous for a business to own its Google Business and Yelp pages, because people go to those platforms for information about businesses and companies. Even if the business owner doesn’t care too much about emerging websites, at some point, it becomes impossible to ignore the value of the page as an asset. Similarly, if you’re setting up any kind of personal or brand web presence, you want to own the same handle on each major platform (Shripriya.com, @Shripriya, medium.com/shripriya, etc). Even if I’m not active on one of these platforms, claiming my “location in the network,” via a profile page, is valuable to me.

Think a few years down the road. As your company grows, what will motivate someone to take ownership of their profile page and invest in it?

- Do they make money?

- Do they make friends?

- Do they find shared interests?

- Do they learn about something they care about?

- Are they entertained?

- Is there something in a user’s profile page that adds value to every other user (or to one other user)?

- Is there a way for one user’s efforts to reduce the effort another user needs to put in to achieve a goal?

These are the situations in which value is created, and that value is attached to a profile page which represents the user’s place in the network. The more obvious this value is to users, the easier it becomes to nudge users onto your platform and keep them there.

TL;DR — these are the key questions as you build this important platform component:

- What can the user control about her profile page? What does the company control? What can other people do via her profile page?

- Should users be anonymous, pseudonymous, or eponymous? Is this a user choice or the company’s choice?

- Does every user have the same kind of profile page?

- *How much interpersonal activity is displayed?

This is crucial if you want network effects, for two main reasons:

- 1. You can’t have a network without nodes in the network. A profile page is how you create and identify those nodes.

- 2. Network effects will start to take off when the profile page itself becomes an asset worth owning.

Many thanks to Andrew Parker and Sara Eshelman for reading drafts and sharing thoughts on this post.

I do not have access to any Clubhouse data, this is conjecture ↩

Who changes?

One of the questions that’s very standard in American filmmaking is: “How does the character change?” It’s all about the character development, their arc, and how the journey through the film has changed them, made them realize something, etc.

There’s another perspective outside of this rigid definition of what makes a good film. My directing professor at NYU, Jay Anania, used to say, “As long as the audience leaves changed, that is enough.”

Pebbles (Koozhangal in Tamil), by director Vinothraj, is set in a small village in Tamil Nadu, India. The village alcoholic drags his son along on his mission to retrieve his wife and daughter from her childhood village a few miles away.

The film is an observation of that quest.

The director makes three significant choices:

- The film is an observation.

- The film is hyper-stylized. The world is scantly populated and extremely quiet. Both these choices do not reflect the reality of the world, but serve to elevate the observational element, keep the focus on the protagonists. They also result in an ever-present tension.

- The cinematography is stellar. I might go so far as to say this has the boldest cinematography choices I’ve seen in a long time. For example, in one scene where the father and son walk to the village, the boy picks up a broken piece of a mirror. As the boy plays with it, we see the reflection of light on a large rock and the landscape as he walks along.

Through the 75-minute movie, we learn about the protagonists and the world. There is no arc, no inciting incident, none of the characters have a realization or change.

At the end of the film, it is the audience that leaves changed. And that is what makes this film so impressive.

What Goes On A Pedestal Must Come Off

If there’s anything everyone can agree on, it’s that we often miss the nuances of things. Politics, social issues, momentum investing. It seems very black and white, all or nothing. And that’s not entirely a new thing—but it concerns me when it gets applied to individuals who we either lionize or vilify. In a world that’s increasingly complex, we should be increasingly nuanced. Instead, it often seems like we’re becoming less nuanced.

“You should never meet your heroes” is an adage that’s been around for quite a while. But it should go further.

In the film world, some of the most creative auteurs are huge assholes. They treat people like shit. In fact, it can go well beyond that as some of the #metoo saga has shown. It’s true in the classical music world, in the arts (painting, sculpture), and probably in every field. Gandhi, who brought freedom from tyranny to hundreds of millions of people and inspired MLK, participated in freakish experimentation in sexual stoicism.

In tech, the concept of heroes has long been a problem. Of course, there are amazing individuals who are pushing the world forward by being creative, bold, enterprising… by being geniuses in their field. The problem, though, is that we conflate capability or achievement in one sphere with everything else, including being a good person, a good human being, or someone who’s smart about everything else, like the arts. Why do we care what an accomplished CEO or investor thinks about all these other areas that they have nothing to do with? And more importantly, why do we give them the credence of a demigod?

It’s a truism that we only see a sliver of these people’s lives, and often, it’s the sliver they deliberately want us to see. If someone has the image of being infallible, that’s fiction. No one is flawless.

Whatever goes on a pedestal must come off. At minimum, it’s going to come down for cleaning. No pedestal is permanent. Putting people on pedestals doesn’t serve us, and it also doesn’t serve them, because it only makes things worse when they come crashing down.

There are so many smart people in the world. Some of the smartest people I’ve worked with are not even on social media. So they can’t become heroes in a world where followers, controversial hot takes, fragile egos, and pithy one-liners rule the world. My heroes are those who I know well, the people who I respect for their ethics and how they live their lives, not just their public accomplishments. But even then, I try to think of them as heroes in one sphere—in one part of life that I’m aware of.

Will People Pay for Just One Flower?

My friend Sanjay Subrahmanyan is one of the top classical vocalists of India. Before Covid, he regularly performed at South India’s equivalent of Lincoln Center, for crowds of almost 2,000. After countless delayed and cancelled concerts, Sanjay eventually decided to go rogue. In January 2021, he launched a YouTube channel membership—a direct-to-consumer plan.

I thought this was a fascinating move, especially for someone whose audience consists predominantly of Baby Boomers, in the relatively conservative industry of Carnatic music

Sanjay described the change to me like this:

“In the past, the Music Academy and 10-15 other organizations would come together to produce one huge music festival. It’s a 30-day extravaganza with 5 concerts per venue per day. This was like being one flower in a bouquet. People are used to paying for the bouquet. Now, I’m asking them to pay for just one flower.”

Sanjay has three tiers of subscribers, using YouTube memberships. The basic tier is free, and everyone receives access to hundreds of archived recordings that Sanjay and his wife Aarthi have been collecting since the early 2000s. There are thousands of hours of these, and he releases more regularly. The second tier ($1 per month) gets a preview of the new uploads before they’re released to everyone else. The top tier ($10 per month) gets a brand-new concert every month, released to them exclusively. Sanjay gets together his accompanists, heads to a recording studio with a video and audio team, and performs and records a 90 minute concert each month.

Before the pandemic, the online world and business was a hobby for him. From discovering usenets in 1995 on a trip to the US to releasing songs on mp3s in the late nineties, he’s been personally fascinated with using and discovering new technology and exploring what was out there for his profession. But he considers it just dabbling. He never looked at online as a full-time business proposition because he was busy performing 50 to 60 concerts a year, all through inbound invitations. He was an early user of Gumroad and had also been releasing albums on Spotify and making a lot of his performances free on YouTube.

“But over the last three or four years,” Sanjay told me, “I realized the trend was more toward video: people want to see you, especially during the pandemic. I picked YouTube partly for that reason, and partly because it was very simple for subscribers. Most of my fans are in their 60s, so they need something simpler than Patreon or Gumroad. That’s why I use YouTube, even though their cut is 30%.”

A few takeaways from this:

First, ease is important; fans will be more open to paying if it’s really easy for them to sign up and access their stuff, so a platform where they already spend time has an added benefit.

Second, existing networks compound; YouTube is a compounding engine for Sanjay’s subscriber base. He has ~30,000 basic subscribers on YouTube. Converting a few of these people to paying subscribers and providing the rest with fresh content will reap dividends over time.

Third, it’s so important to keep a record of everything, so you have plenty of content to share and choose from. For a performer, it’s obvious how to do so – record everything. But for a visual artist, don’t discard “work in process” or little day-to-day projects. For a writer, even snippets that show how you work can be valuable. It’s not a big, fully wrapped deliverable, but it’s work you still created.

Sanjay realized that he had to share his performances with his audiences to stay relevant. He also realized he deeply missed performing. Performers have to perform!

To go from singing 60 concerts a year—which included planning and preparing, coordinating with accompanists, experiencing the joy of the performance and the gratitude of having an audience appreciate it—down to zero concerts in three months is very hard for someone who performs at the highest levels. And to lose a year of performance revenue in his prime was not easy. But it was a forcing function that made him take the leap into developing a direct relationship with his audience.

Sanjay has had to evolve from a performer focused on his craft to someone who has to focus on the business side of the equation. To use his creativity and apply it to areas like logistics and business operations, to marketing and branding.

This has unlocked new forms of creativity for him. While he’s primarily a performer of existing compositions, he has on occasion arranged new compositions. But these were all still vocal arrangements that were delivered during live concerts. In the past couple of months, he’s explored how to use video more creatively. He recently created a new arrangement of a beautiful poem called “Tamizhan endroru inamundu,” which means “Tamilians are a tribe.” His collaborators filmed it and developed a visual treatment for the poem.

For creators, will the hybrid model will become the default? Will more artists go rogue like Sanjay? Who are the kinds of creators who will be able to do this? Sanjay is typically a performer of music that other people have composed, so it’s been a relatively low-lift for him to produce new content. What about filmmakers, who have to bring a much bigger team together with (almost always) a bigger expenditure/budget? What about writers or composers, where each piece may take months and many drafts before it’s ready to share?

The “creator” economy is a very broad term that covers creators who are so different from each other in terms of frequency of creation, complexity of creation, ability to share work in progress, and so many other dimensions. It’s in the nuance of the differences that opportunities exist for both creators and for the tech solutions that serve them. Where will we go next?

Apollo’s Arrow

We’ve all been thinking about it: how the pandemic has affected us, which of the changes we’ve experienced will become permanent, and which old ways we will embrace (literally and figuratively) with open arms.

To get another point of view, I read Apollo’s Arrow by Nicholas A. Christakis, a physician and sociologist at Yale. The book covers the first six months of the pandemic, before viable vaccine candidates emerged. It traces the history of prior pandemics and was a useful read to help inform what may come next.

I ended up with a lot of questions.

The Government and self-reliance

Many of us thought the federal government (most of the time, but especially from 2016-2020) and state governments are generally incompetent. The pandemic proved us right.

- Will people trust government less? Or will trust be limited to certain domains?

- If the answer to the first question is “likely”, then will people try to become more self-reliant or reliant on a smaller (perhaps hyperlocal) community? How will this trend manifest?

- Have we lost so much faith in government that we will all become preppers in some fashion?

- Will we build the capabilities to live off the grid (at least for a few days), grow our own food, know the basics of saving a life (CPR)? Is this progress or is this regression?

- What will be the technological advances that helps make sure it’s progress?

Christakis talks about how mutual aid societies sprung up to help people. Volunteers shopping for seniors, stitching masks, staffing food banks, etc. These efforts likely had a material impact on thousands of people. Will this lead to more community self-reliance? In the NY Times last week, there was an opinion piece on mutual aid efforts in Chicago. While the piece has a political bent, this paragraph can stand alone, regardless of your politics:

In these projects we see glimpses of a society where we meet one another’s needs, not with shame but with the sense that contributing is an essential thing we do for one another. These are the practices that keep us safe.

Work and learning

Anyone who could work from home did. Those of us in that could are very lucky—those doing manual labor, delivery, medical procedures, basically all “essential workers”, ended up putting their lives in danger in order to get paid and do their jobs. No one believes that we’ll go back to “how it was before”.

- Will work become more all-consuming and “always on,” or less? If work becomes truly flexible, for some types of workers (like parents), the flexibility could be invaluable and a competitive advantage to companies that offer this flexibility.

- Will people who are capable for self-structuring thrive in this world?

- Will more people spend time thinking through and defining the “proper place” of work in their lives?

- Will (business) travel be reserved for special occasions versus the grind of “yeah, I’m in NYC twice a month”?

- Will business conferences be hybrid, with more experiential attractions to get a small number of people to show up in person?

- How will talent-driven globalization reshape companies? My partner Marc wrote about this.

- For services that can be provided remotely, will States change licensing rules so that anyone in the country can provide services to others? Christakis talks about how this happened with the pandemic because the availability of doctors was so limited. This is a situation where the pandemic moved us forward faster than any government-led effort could.

- Will some medical specializations move entirely online? For example, what’s to say my eye test cannot be completed remotely? And then with remote ordering, glasses and contacts just show up at home.

- What will food retail companies do moving forward? Do we need to have grocery stores people can visit? Or can there be very efficient grocery warehouses for areas and robots deliver whatever we want, whenever we want?

- Some manufacturing may need to be local again. When countries are rushing to save their citizens, everyone else comes second.

- Adults who could work from home during the pandemic, often ended up exploring the world of online learning and courses, filling commuting time with learning instead. Will new models keep emerging as we iterate our way to figuring out what works best for each person?

- Many children were forced to be completely remote, with no interaction with their friends, no in-person sports, or entertainment. How will this affect their view of education and what can be done remotely?

The pandemic showed us that despite all the talk about how education will be remote, all parents wanted kids back in school—for socialization, for effective learning (many kids struggle with remote), and yes, for some semblance of sanity for the adults. But now that schools and educators have figured out the benefits and limitations of remote, maybe we can find the most effective ways to deploy a hybrid solution in the future.

Much like learning, the way that work will change will also have nuance and complexity, and not everything will be obvious a priori. We can only see the very tip of the spear, in terms of how work will change.

Human connection & creativity

We have certainly separated the introverts from the extroverts! Even the introverts are ready for some socialization. But more fundamentally, we’ve adopted practices and tools as a species in a way that’s more widespread than before. This is bound to affect how we work and play together in the future. The prolonged isolation could also change our priorities in the short or long term, when it comes to connecting with others.

- Will in-person / human / analog connections & experiences come roaring back, or will people want a hybrid?

- In what ways will people change their perception or belief about what matters or what’s valuable? Will people become more philosophical? Focus on on spirituality? Embark on a quest for truth?

- We’ve seen new forms of collaboration. Christakis talks about how the NY Philharmonic Orchestra each recorded their own contributions separately and it was joined together to share with the world. How will people continue to collaborate, perhaps around the world?https://youtu.be/D3UW218_zPo

- How might philanthropy evolve, now that we know we can have an impact on every connected person on earth?

- There were new forms of dating, and new forms of connecting. People felt more vulnerable since we were all going through the same thing. And that led to people sharing more. How will we maintain the vulnerability, honesty, and compassion as we move past the pandemic?

The roaring twenties, a century ago, were the outcome of a major cataclysm. Will we see that again? I’d argue that while we will see the extreme desire for experiences, I’m not sure we will see as much ostentatious consumption. We have a sustainability crisis on our hands — I’m hopeful that the consumption and excesses will be a bit more restrained this time around, perhaps more focused on human connection and the experiences that enable that.

Sustainability

One of the things that stuck with me was Christakis’ definition of cumulative culture:

Human beings endlessly contribute to the accumulated wealth of knowledge that belongs to humanity, and each generation is generally born into greater such wealth.

Part of why we have vaccines so quickly is because of cumulative culture. It has been combined with global collaboration from scientists who focused on sharing data quickly, with everyone who needed it, and global altruism from the armies of volunteers who have tried these vaccines early stages of development so that more vulnerable populations could receive something tested, stable, and safe.

- Can we apply this level of collaboration and altruism to the problems of climate and sustainability? Or because it is a less obvious problem than a pandemic that kills hundreds of thousands in few months, will we continue to ignore the problem? How can we bring more urgency to sustainability?

- We know that density of living is good for sustainability. How has the pandemic affected this?

- Will cities remerge as the way to live after a year where many people moved out of the densest cities? Will cities make public spaces a priority and ensure that their citizens have a cornucopia of delights to experience when they leave their apartment buildings? What new services will emerge if this happens?

- Will people pay more attention to the hidden costs of their actions and be willing to sacrifice? Will groups of people collaborate to usher in new norms of climate responsibility?

Much like the pandemic, sustainability needs everyone to collaborate, to look at how we live, and perhaps even sacrifice a little bit.

Christakis recounts that seismologist Thomas Lecocq noticed that at the very start of the pandemic, when almost all travel and industry came to a halt

“…the Earth was suddenly still. Every day, as we humans operate our factories, drive our cars, even simply walk on our sidewalks, we rattle the planet. Incredibly, these rattles can be detected as if they were infinitesimal earthquakes. And they had stopped. […] The coronavirus had changed the way the Earth moved.”

If companies and people change our behavior, just a little, those small changes add up to a bigger impact on our planet. We have to find a more sustainable path forward so that we don’t lead to the most vulnerable populations bearing the brunt of climate change.

While the book was useful in tracing the history of pandemics—the ones we’ve heard of and the less familiar ones—the most useful aspect of it was that it gave me some time and space to think about what comes next. More questions than answers, but perhaps a good place to start.

What questions are on your mind?