You’re a startup founder. You’ve gone through the rollercoaster, and things are going really well. Now you need to scale, because you’re overwhelmed with work, barely surviving.

Enter the “shiny-object savior.”

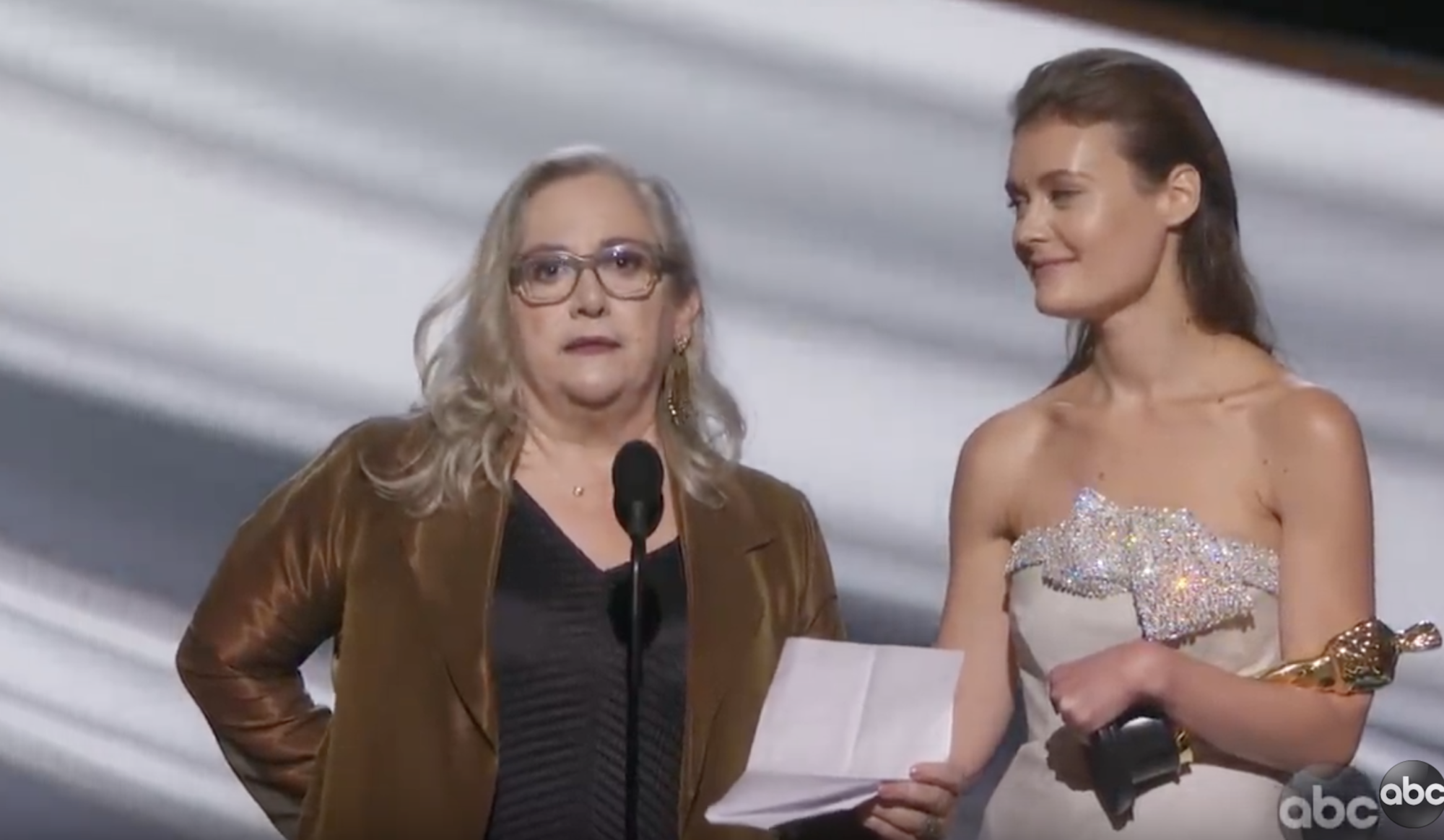

This person is [insert letter]VP at [insert big name company]. She seems to have it all – the titles, the accolades, the network, and could be the one (and only) person to actualize the company’s potential.

But there’s a risk that if they aren’t the right person for the job, they could significantly derail you both in terms of your milestones and in terms of your company’s culture.

Before you get starry-eyed, here’s the one question you should really ask yourself: Can they be successful in your company?

Here are the key factors to think about to answer this question.

They might not have accomplished anything meaningful/been successful.

Dig into accomplishments, not just the titles on the resume. A glossy resume could just be the result of their artfully job-hopping to make them seem like they are on an upward trajectory. Be wary of people who have never gotten a promotion within a company, as promotions are one sign of recognition for a job well done.

They might only function well within a certain culture.

Even if someone was able to get promoted or be successful at one company, they might be a great fit with that company culture—and only that culture. If that’s your culture, great. Hire them.

If the culture is different from what you are trying to build, be aware that they are going to bring elements of the old culture with them, because that’s the way they know how to thrive.

They might not have a growth mindset.

In my experience, successful startups need to be constantly learning, constantly ensuring product-market fit and constantly looking for new avenues of growth.

For a leader to thrive in an environment like this, they have to be able to navigate changes and know when to change course appropriately and when to stick to the plan. Have them tell you about a time when new data caused them to do something differently. Have them tell you about their world view, what has shaped it and how they think about changing that view.

Bottom line: Do not rush a big hire. Don’t get starry-eyed over a resume. Dig deep, know who they are, and do your references. The time spent upfront will significantly increase your chances of hiring the right person.