View on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/p/CE3V2d7pdvB/

View on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/p/CE3V2d7pdvB/

In my experience, the best leaders ask the questions that matter. And the questions that matter are the key to driving the organization forward.

As the founder or leader, you’re in a unique position with a wider, more all-encompassing perspective. You can see the vision of where you need to be in 3 years and in 5 years, the reality of your bank balance and fundraising, and the sense of the morale of the organization. You’re the only one with all this information floating in front of you as you chart a path forward.

What do you do with that?

The best leaders use their unique position not only to make objective observations on the state of the business, but to determine the right questions to ask the team. They use these questions to guide the organization towards the most important goals.

Imagine a product team that has spent the last few weeks designing a feature. They’re excited to present it to you. It’s a great feature — but based on where things stand, it’s not the highest priority. While you know that, you have to communicate it in a way that’s productive.

This is where you ask the questions that matter. By asking the right questions, you won’t just tell people what you see; you’ll help them see it, too. You’ll keep them on track while keeping them motivated.

A few of the questions that matter, in this example:

Instead of command and control, questions help the team think for themselves. It’s the Socratic method for effective orgs. The caveat is that in an emergency or a time crunch, being directive is fine. It may be needed. But organizations that always rely on one person to make decisions end up paralyzed and ineffective.

I once worked with a senior leader who did exactly this. If someone came to her saying a deadline “could not” be met, she’d find the right people and ask the questions that mattered. By doing that, she’d help people figure out how to circumvent the bottleneck. She ensured that the things that moved the company forward, moved forward. It was amazing to see how “impossible” things, once she’d pinpointed the right questions, got done.

The same is true for investors. I find the best investors ask founders questions that make them think about the world differently, change the lens, expand the set of options in front of them with an interesting re-frame.

Asking the right questions indicates a level of thought, knowledge, and facility with the world you are dealing with. A leader asking the right questions can help an organization come up with creative solutions, hit their goals, expand their view of the world, grow to become more self-sufficient, and by doing so, move the organization toward that long-term vision.

View on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/p/CEiwsFepGn1/

These are some guidelines for an improv class.

This is also startups.

Your startup is an improv class.

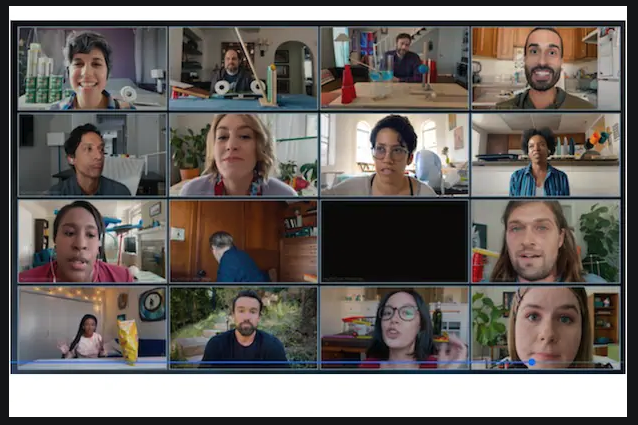

View on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/p/CEQqGKjpTLO/

Human beings are amazing. A mere two weeks after the lockdown started, most people had adapted to a remote world. Kids were learning soccer on Zoom, personal trainers adapted, cooking and baking classes moved to zoom—but I really did not expect theater and filmmaking to adapt in this world.

But, adapt they did. Zoomtheater and Zoommovies are a thing now, 4 months into the pandemic—for example, Host is a horror movie, made on Zoom.

Are these pieces any good? Well, it depends — film, which is asynchronous (i.e. shot and edited before the viewer sees it), can be just as good. For theater, which is delivered in real time, the remote version is not as good as when the cast and crew are in the same location. But the ability to adapt, the ability to even try this, makes me optimistic.

For a polished spin on quarantine filming, look at Mythic Quest, which is on Apple TV. They were filming the second season when the pandemic shut things down. This article outlines what the crew and cast did to shoot a “pandemic” episode that is part of Season 1. They used iPhones with prosumer film software, mics, and shot in all natural light, since lighting is one of the harder parts of filmmaking. They then edited it together to make it look like it was shot on Zoom.

On the other hand, some of Princess Bride’s celebrity cast decided to make a fan fiction, and it’s very clear that it’s shot by non-professionals, embracing the reality of shooting in different locations, with no crew.

In a scene with Diego Luna and Jack Black, they create continuity from two different locations in amazing ways: Diego throws down a green rope tried to a tree in his house and Jack, who is lying on a set of stairs in his house, grabs a hose that is thrown down to him. Diego lifts, Jack clambers, until finally, Jack is back at the top of the mountain (stairs). It’s really well done!

This would never have been considered acceptable pre-pandemic, but with a new set of rules for the world, there’s a new set of expectations. All film-watching requires the “willing suspension of disbelief,” and for these pandemic-pictures (panpics?), the suspension of disbelief has to be extended. But they are so entertaining!

Theater, unlike film, is synchronous – everything is live. This makes it much harder to adapt to a remote environment. While in film, you can do an extreme close up to show the twitch of an eyebrow, theater acting is “bigger,” so that the person in the last row can have the same read of a scene as someone sitting in the front. So Zoomtheater and the innovations there are harder to adapt to the pandemic. But theater has adapted, too. And if the pandemic stretches out, theater will have to continue to adapt. Imagine if there was a plugin that:

It’s entirely possible that this could happen. Because despite the insanity in the world around them, humans continue to create, continue to innovate, continue to live lives of hope and splendor. Constraints make them innovate in ways that they wouldn’t have thought to before.

The same is true for startups. Startups have to startup. And the first requirement of startupping is surviving. But the very best startups, like the best creators, use constraints to innovate and thrive, offering customers an unexpected, delightful solution that moves us all forward.

View on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/p/CECvpxeptEz/

Chanel Miller said her New Year’s resolution for 2020 was to fail as much as possible.

“Making things that are really crappy and undeveloped until maybe they can be good. I’m way too young to confine myself to one lane and lose the ability to openly experiment.”

This is exactly how a the first draft of a film script develops. Characters and ideas float around in your head, and one day, they’re done with the floating and demand to live on the page. The script gets written, and when you’re done… it’s shitty. It’s embarrassing, you don’t want to show it to anyone, and you wonder how on earth your magical characters and ideas amounted to this pile of doodoo on the page.

But, it’s really important to have this first draft. Because as Miller said, yes, it’s crappy and undeveloped, but you need the crappy and undeveloped to have hope for the good and the great.

Struggling, wrangling, failing, crying, working, pushing forward allows your characters and your story to breathe, thrive, and for the bones to slowly emerge from the pile. Experimenting openly, taking the story in unexpected directions, adding or removing key characters, and messing around with no pressure allows the sparks of creativity that makes the script sing.

Every creator needs that messy time.

The same is true for startup creators. Ideas for a product form in your head over time, sometimes over years. Then one day, you’re ready to put it on the “page” — to code something, to craft something. And it may be a sloppy, messy ball of hair, mud, and hope. Don’t clean it up, polish, and shine it in order to raise money too early.

Love your messy stage, because it is so important to relish that stage. You can only do it once for each startup, and it’s when experimentation, ideation, hanging out, and trying weird things is entirely possible. It’s where ugly is awesome.

At some point, a screenwriter will have to share the script with producers. At some point, you have to share your startup with users and, if you want, with investors. If things go well, they love it, and you build an amazing company. Fantastic.

If you’ve grown your company into a wonderfully world-changing one, it’s worth finding ways to go back to being messy. Get into small groups. Make room for experimentation with ugly, creative things that may fail, because that can lead to new lines of growth. If you have the urge to start again, you could start another company and embrace the new ugly ball of mess. Whatever path you follow, the messy part of creation can be the the best part of creation, and the challenge of it makes your ideas and your company better.

View on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/p/CDvKVnOpKZd/

Every August, US filmmakers rush to make the Sundance Film Festival deadline. And in early December, Sundance announces its lineup. The day before, everyone is equal—all aspiring filmmakers. But the moment Sundance announces, the wheat is separated from the chaff. There are those who will have a film that “premiered at Sundance,” and… there are the other mere mortals. Both groups will now be treated differently as expectations start to diverge.

While companies are less of a lemming-like march to the cliff than film festival applicants, similar rules apply. After a company goes down in flames, or after you get fired, the same thing happens. The very next day, there’s a sense that you’re a different person.

In both cases, I see a similar pattern: people define themselves (and each other) in terms of their successes and failures. But both success and failure are transient and ephemeral. They can both be taken away, forgotten, or overcome. Successes and failures aren’t who you are.

Perhaps, instead of letting successes and failures define you, define yourself according to something no one can take away, something you cannot lose.

If you can lose your job, you are not your job or your job title. If you can lose company, you are not your company. If you always need permission to create or make a film, you are not a creator or filmmaker.

A couple of years ago, someone asked me if I would view myself as a failure if I failed at my job as a venture investor. My answer was yes. I explained that my job is a huge part of who I am, and if I fail at it, yes, I would be a failure.

Since that conversation, I’ve come to a more nuanced view of the world. I wouldn’t say to a founder, “If your company fails, you are a failure.” Quite the opposite. You are not your company, and regardless of whether you took it public or closed it down, you are separate from the entity that is your company.

So, if not by those ephemeral things, how can you define yourself?

Despite the transience, we let success and failure have such a huge impact on us. Depending on how we deal with it, they can change our life trajectories. But these things still aren’t who we are. Who you are is the amalgam of personal characteristics that make you up. It’s what you learn from success and failure. It’s how you deal with it, and what you go on to do with it. That’s what no one can take away from you, and that’s what makes you who you are.